3 Common Cucumber Mistakes You've Probably Made

Gotchas that bit me while I was busy chewing Cucumber.

Cucumber specification can be a living documentation that describe the software as a whole and exercises all parts of it. It can not only catch regression bugs and provide confidence for refactoring and improvements, but also can be a real specification of the software that is always up-to-date with the software itself.

But as with everything there is no free lunch, these specs and tests doesn't come without a price. If done carelessly, not only the cost can easily outweigh the benefits, but it can undermine the team's trust in automated testing.

I have been using Cucumber in quite a few projects. I've had the chance to introduce it to legacy applications, and starting greenfield projects with it. I made all kinds of mistakes, and see others do them as well.

Below is a list of the most important gotchas I've seen in the last couple years working with Cucumber.

1. Too general steps

When I first got my hands on Cucumber on a real project, I started to write scenarios like this one:

Given I am on the Accounts page

And I click on the New button

Then I should see the New User dialog

I rejoiced when I made it pass, and at that point I was absolutely sure that I can express the whole specification with a few really general glue methods. So I continued:

Scenario: Creating a new Account

Given I am on the Accounts page

And I click on the New button

And I fill user_name with test_user

And I fill email with test@test

And I click on the Submit button

Then I should see test_user in the users list

Indeed, I was really successful with keeping my glue code base small. But there was a price I've paid. My specifications were boring, no one ever wanted to read them. Even if someone wrestled his way through it, the meaningful details got lost between the lines of predictable, spoon-fed sentences.

The wording of the feature description above is more like a checklist of test steps rather than a real specification. It's tied to the details of the implementation. It depends on the User Interface layout, and it contains a lot of incidental details that is not important from the business requirement that it is trying to describe ("Creating a new Account").

This makes the feature description less useful as a specification, and more brittle as an automated test. Possibly it has to be modified even when minor technical changes are introduced to the application. For example if we were to add an extra confirmation step before allowing the user to submit the form, we would have to modify the specification as well.

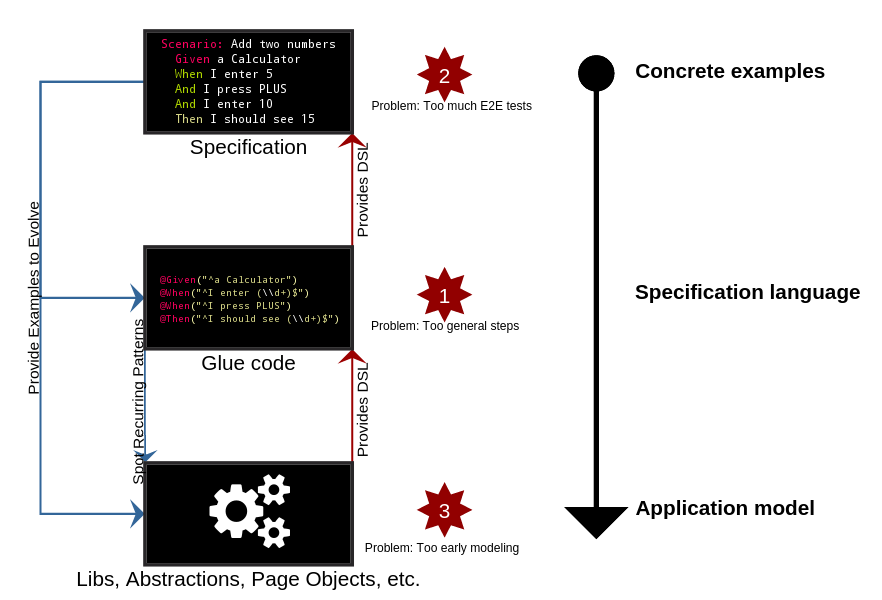

The glue code defines the specification language for your business domain, it determines how you describe things. Keeping this language small might be good to achieve a unified vocabulary, as you would rarely want to express the same thing in more than one way. But overdoing it can be harmful. In a too limited vocabulary it will be hard to meaningfully express anything.

Also try to take into account what elements the language should contain. Is 'I click on the <X> button' worth being a fundamental part of the specification language of the Accounts feature? This is how it would be expressed in a real specification?

I think it's best to simply write the specification without thinking about the glue code, just thinking about the business requirements and the application. Strive for specification that describes the what rather than the how. Also writing glue code is usually easy, there is no need to optimize for the code size. Don't generalize, be descriptive.

2. Too much end-to-end tests

To make things worse, I wrote not only boring, but long, comprehensive specification for all the features. (In this case the features were done already, we added Cucumber later.) It seemed like a good idea, as with my 'specification language' consisted of a few patterns, they were dead simple to write, so I thought it's better to cover more.

I started to document and test every trivial feature, every less important edge case. Turns out using Scenario Outlines are a really great way to quickly produce lot's of meaningless test cases.

This is of course not only bad for the reader of the specification, but it has it's cost in testing as well, if it drives end-to-end (E2E) tests, for example through a browser. Compared to unit and integration tests, they are slow, fragile and more flaky, thus need more maintenance. They are more expensive than tests with smaller scope.

But there are many benefits of E2E tests. They can be great to verify that the application really works in production-like circumstances. Because they tend to test the most outer interfaces of the application, they more likely to contain less implementation detail than a unit or integration test, so they are more resistant to change and are a great help during refactoring.

It's important to find a healthy balance in the various test types. One reasonable concept is the Test Pyramid.

I think it's best to write one E2E test for each important use-case of the application, and many integration and unit tests that move a step further to the implementation in each topic.

For example, in the case of Accounts, it might be a good approach to write one feature description in the Cucumber specification to verify that the users can upload avatar images, and create a separate set of integration tests to check that the file uploading mechanism can handle different file types. Zooming into the details one can write more tests with even smaller scope, for example to throughly test the filename and file size validators.

It's always worth to consider what benefit additional E2E tests and spec provide.

3. Too early modeling

The specification and the related test suite is an application on it's own. Its purpose is to discover the application under test through it's outer (typically user-) interface. The feature specification express what we expect from that application, and the glue code vivifies it in form of automated tests.

The glue code, and any abstractions it's using are to model the application's behaviour from the user's perspective. This model evolves through the discoveries made when adding new use-cases to the test suite, while those tests are limited by the things the model can express.

The model can't unfold without the insights provided by the use-cases, it can only grow blindly in it's limited knowledge. Similarly, just writing tests and not building abstractions over the glue-code doesn't pay off in the long run. One might quickly end up with lot's of copy-pasted code that is hard to maintain.

Balancing between over-engineering and not engineering at all is not specific to testing code, but writing tests require a different mindset than writing good production code, so it's easy to get sidetracked.

I think it's better to start small. Encode concrete examples in the glue code, don't start building an all-round model just for one use-case. After a while review the tests: what information does it provide about your application? What are the recurring patterns? How could the model encode it more appropriately? Don't just try to eliminate copy-paste, aim to create a consistent vocabulary that the glue code can use to be more expressive.

The Page Object design pattern is really worth taking a look at for inspiration, but I would advise against using upfront. In my experience it pays off to apply architecture in testing code strategically, where it is needed.

Conclusion

Cucumber and end-to-end tests are great tools, addressing problems that commonly arise in typically every project as they get bigger - usually problems related to scalability. They help developers to make changes more confidently, and facilitate internal communication and even communication with the client. They can be a living, always up-to-date documentation of the application.

They allow more developers to work on a project without breaking each other's code, less communication overhead, and they make the project more accessible to new members. These benefits are huge for both open and closed source software.

Even if they require effort to build, and maybe even more effort to maintain, it's worth to apply them at least in the most important parts of every system that is to grow beyond a certain point.